More Information

Submitted: December 13, 2022 | Approved: December 22, 2022 | Published: December 23, 2022

How to cite this article: Hyun Y, You M. The necessity of emotion management for the general public: a comparison of diagnostic changes in two anger-related psychiatric disorders. Arch Psychiatr Ment Health. 2022; 6: 048-051.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001044

Copyright License: © 2022 Hyun Y, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Hwabyung; Intermittent explosive disorder; Emotion management; Anger; Mental health

The necessity of emotion management for the general public: a comparison of diagnostic changes in two anger-related psychiatric disorders

Yoorim Hyun1 and Myoungsoon You1,2*

1Department of Health Policy Research, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, Sejong 30147, South Korea

2Department of Public Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, South Korea

*Address for Correspondence: Myoungsoon You, Department of Public Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Gwanak-ro, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 08826, South Korea, Email: msyou@snu.ac.kr

Although emotion management is essential to mental health, public health has not paid much attention to emotional conditions or disorders. By analyzing a nine-year diagnostic trend and sociodemographic characteristics of two mental disorders: Hwabyung and Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), this study demonstrated the importance of managing emotions precautionarily.

Data reconstructed from the National Health Insurance Service were used to analyze the yearly diagnostic trend in the two mental disorders characterized by anger.

Hwabyung was more common among women and middle-aged individuals, despite the varied number of diagnoses by year. Between 2010 and 2018, IED diagnoses gradually rose, with the average rate of increase the highest in the 20s for male IED diagnoses in 2017. The low prevalence of the IED in Korea compared to other Western countries and the gender and age differences in both Hwabyung and IED diagnoses suggest the role of cultural influences related to emotions (or emotional management).

Especially in light of the world’s emphasis on resilience to COVID-19, these results indicate how public emotional management is essential during stressful situations. The results also highlight the need for community mental health programs tailored to gender and age.

The 3P model of public health emphasizes the prevention of disease, the promotion of health, and the protection of vulnerable populations [1]. It is essential to keep the general population mentally and emotionally well-managed to prevent mental health diseases and related burdens. Though emotions play a significant role in promoting mental health, public health has paid scant attention to the emotional conditions of the population or the disorders associated with those emotions. This study focuses on anger by examining two anger-related diseases: Hwabyung and Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED). The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the need to manage emotions precautionarily by analyzing a nine-year diagnostic trend and sociodemographic characteristics of two mental disorders.

According to American Medical Association, Hwabyung is a mental disorder that is nonpsychotic within a Korean cultural context that is characterized by the chronic suppression of distressing emotions and the endurance of oppressive and traumatic experiences [2]. There are several factors contributing to Koreans’ suppression of emotions. First, Confucianism has been the moral foundation of Korean society for hundreds of years. Confucianism’s priority is maintaining dignity and pride, so it is considered shameful to express feelings and embarrassing to engage in confrontation [3]. Familiar collectivism is considered to be one of the most dominant cultural principles in Korean society. This principle gives group needs priority over individual needs, which also plays a role in suppressing an individual’s anger or negative feelings. Those who display anger or uncomfortable feelings are considered morally unacceptable because it can jeopardize cultural conformity. A result of the accumulation of suppressing emotions is Hwabyung [4].

Another mental disorder that mainly addresses anger is IED. Patients with IED present high levels of a minor (i.e., verbal aggression or physical aggression without harm) and/or major (i.e., physical aggression with harm) aggression disproportionate to the provocation [5]. A common issue among IED patients is poor emotion regulation [6]. An individual with an IED exhibits both elevated levels of anger [7] and more global difficulties with emotional regulation, such as increased affect intensity and reactivity [8-10]. According to Coccaro and McCloskey [11], IED is a widespread psychological condition that affects about 3% to 5% of the total population in the United States.

To analyze the yearly diagnostic trend in the two mental disorders characterized by anger, we utilized data reconstructed from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). We hypothesized that anger expression would differ by socioeconomic characteristics and analyzed Hwabyung as an anger-in disease and IED as an anger-out disease. South Korea has a social health insurance system, and all Korean citizens must be registered with the NHIS by law. The NHIS data have strength in that it is a national administrative data set covering 98% of the country’s population [12]. However, since the data is a compilation of individual medical records, only each patient’s sociodemographic and medical characteristics can be retrieved by reconstructing the medical records. The patients’ economic status was measured using insurance fee variables by dividing the variable into five groups. This is a reliable estimate of the economic level since South Korea adopted a progressive tax system. Duplicate diagnoses, such as cases in which patients visited the hospital for the same diagnosis more than once, were excluded from the analysis. The National Health Insurance System (No. REQ0000035411) and the Institutional Review Boards of the Seoul National University (IRB No. E2004/001-001) approved the study. All studies were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and STATA SE ver. 13.0 program (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

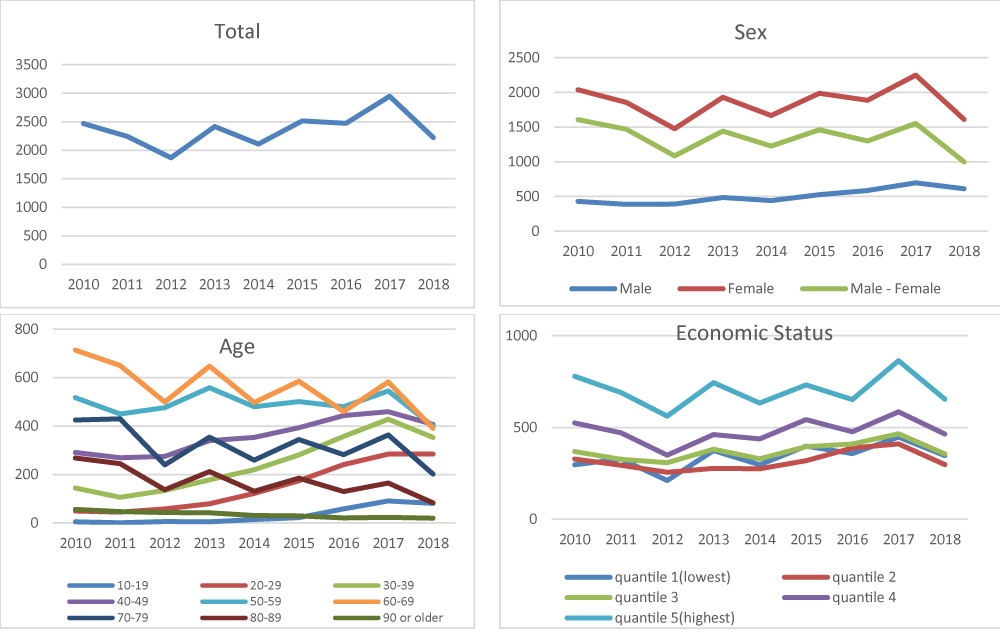

The trend in Hwabyung diagnosis over gender, age, and economic status is illustrated in Figure 1. Although the total number of Hwabyung diagnoses varies annually, the number of diagnoses for females is consistently more significant than for males every year, on average 3.8 times. Hwabyung is more common among individuals between the ages of 50 and 59 and 60 and 69, while it is increasing at a greater rate among individuals between the ages of 20 and 30. Further, Hwabyung diagnoses were highest among individuals with the highest economic status in 2017.

Figure 1: Diagnostic trends in Hwabyung from 2010 to 2018.

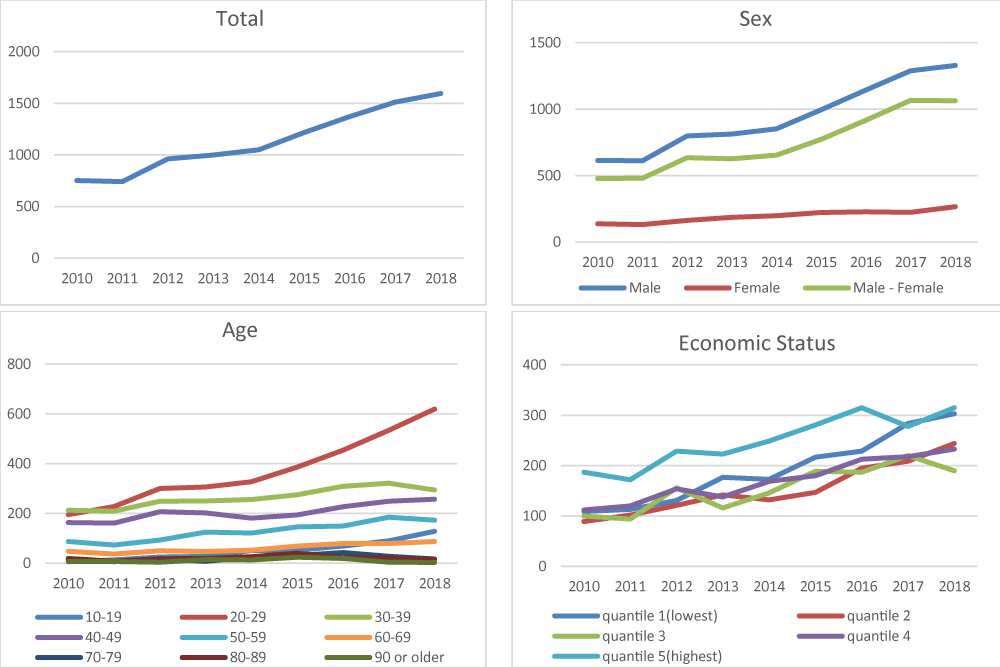

As can be seen in Figure 2, the trend in IED diagnoses across gender, age, and economic status from 2010 to 2018 has gradually risen. Since 2010, the number of IEDs has steadily increased at an average rate of 10.7%. There was a significant increase in male IED diagnoses in 2017, with approximately five times more male IED diagnoses than females, according to subgroup analyses. Based on their age group, the average rate of increase is highest in their 20s, at 45.4%. By economic status, the highest economic status population group consistently had the greatest number of diagnoses in IED since 2010, except in 2017, when the lowest economic status population exceeded the highest economic status group. The lowest economic status has increased faster than other groups, with an average increase rate of 14.3%.

Figure 2: Diagnostic trends in Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), from 2010 to 2018.

Several implications can be drawn from our exploratory comparison of anger disease, Hwabyung and IED. First, while Korea is one of the highest-income countries in East Asia, it has a very low rate of IED diagnoses compared to other Western countries, such as the United States. According to previous studies [13], approximately 5% of the U.S. population is estimated to have IED. Only 700-1,600 IED cases have been reported in Korea, representing less than 0.01% of the entire population. This is significantly low, even compared to Japan, another Asian country that is often compared to Korea. In Japan, IED prevalence is approximately 2.1%. As indicated in a previous study by Hong, et al. (2017), Koreans are more reluctant to seek mental health services even when they are needed, reflecting the cultural context of Korea. Based on the National Mental Health Survey data, they found that while one out of four people experienced mental health problems at least once in their lifetime, only 22.2% of them utilized mental health services. In 2012, another Korean study found that only 11.2% of Koreans reported symptoms of schizophrenia and 42.9% reported symptoms of depression, significantly lower than that of Germans and Swiss, which were respectively 70.2% and 62.2% in Germany and 73.6% and 60.2% in Switzerland [14].

It may be because Koreans are less likely to have mental disorders. However, Asian cultural contexts may also play a role. Studies have shown that Asians have a negative attitude toward mental health problems [15-18]. Asians view mental health problems as something they must endure and overcome on their own. Asians who tend to suppress their emotions are less likely to recognize or admit their mental health needs [19]. This cultural attitude fuels reluctance regarding mental health treatment-seeking behaviors [16-20]. The stigma of mental health problems [15], misconceptions about mental health problems [19], and mental health illiteracy may also shape negative attitudes [21]. An open social atmosphere and public and private efforts to encourage individuals to seek treatment are also required for early detection and proactive mental health management.

Second, by gender, Hwabyung was more frequent in females than in males, and IED was more frequent in males than in females. Previous studies also reported a higher prevalence of Hwabyung in females than in males [22]. Reflecting on the key difference in the direction of anger expression between Hwabyung, as internalizing anger (‘anger in), and IED, as externalizing anger (‘angering-out’), the gender difference in the prevalence of Hwabyung may be explained in relation to gender roles. In general, the socialization of gender roles significantly reinforces males to be aggressive and females to care for others’ needs [23,24]. The internalization of anger (‘anger in) is not an exception for Korean women regarding the cultural context in which they are situated at. Previous research found that Koreans are taught to express their anger differently in the course of their developmental stage, in that men’s externalization of anger is rather accepted in a generous manner from an early age, whereas women are taught to suppress their anger [25].

Especially women in their 50s and 60s showed a high number of diagnoses in Hwabyung. This is consistent with the previous findings that Hwabyung is suffered mainly by middle-aged women in Korea [26-28]. The high number of diagnoses of Hwabyung in middle-aged women can be related to the context in which they are placed in terms of Confucious norm-based Korean society. For example, Kim, et al. [29] have shown how women’s Hwabyung is related to their sex role in Korean society by explaining that a married woman’s discontent with the oppressive household rule of her mother-in-law is expressed through Hwabyung [29]. Shin, et al. (2014) have also examined how the internalization of anger(‘anger in) contributes to Hwabyung in middle-aged Korean women, identifying internalized, lowered self-esteem and negative life events as the primary causes of Hwabyung [30]. It follows that Hwabyung management should be tailored to middle-aged women. For instance, a recent study shows that group-based intervention is especially effective in Hwabyung treatment for middle-aged women. According to Kim, et al. [31], group-based therapy empowers middle-aged female Hwabyung patients to speak out and share their stories with others with similar gender-role development [31]. Another study also suggested that group treatment was beneficial in that patients received empathy and support from others but also encouraged them to express empathy and support.

Finally, IED was observed to be most diagnosed in their 20s. Previous literature has identified that anger in their 20s is highly related to their stress about getting a job. Others also suggested that the reason for the recent increase in the diagnosis of depression and anxiety among young people in their twenties is the environment surrounding them, that is, our society, such as job shortages, extreme competition, wealth polarization, inequality, and excessive stress. Since IED patients frequently show symptoms such as depression and anxiety, it is worthy of consideration. While the primary goal for young adults in Korea is finding a job, stress comes from high job insecurity and financial strain on supporting themselves independently of their parents’ attributes, in great part to their anger [32]. Financial aid policies should be expanded to assist them, as well as mental health promotion programs aimed at improving their emotional health. For the younger generation, in addition to one-on-one psychological counseling services with counselors, providing an online space where they can freely express their negative emotions experienced due to daily stress is one way to approach the problem since the young generation has shown to prefer online-based communication in dealing with their mental distress [33].

The current analysis has several limitations, including the inability to categorize primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals, as well as the absence of provider factors. Since our analysis is exploratory, further research with a comparative analysis between Hwabyung and IED would be helpful. We recommend that future research consider additional variables that can reflect the social and cultural factors and provider factor variables such as hospital type.

Despite such limitations, our research is informative in that we have identified sociodemographic characteristics in relation to expressing emotions, especially anger, by examining the two mental disorders. Despite the fact that the public was equally affected by the suspension of social activities caused by COVID-19, it is implied that psychological distress will differ by population group. The results of our research suggest strengthening emotional management capacity, especially through diversified communication and community-based programs that consider gender and age, as a response to the mental health effects of COVID-19.

- Nathwani S, Rahman N. The 3 P's model enhancing patient safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Surg. 2021 Aug;14(3):246-254. doi: 10.1111/ors.12607. Epub 2021 Feb 17. PMID: 33821170; PMCID: PMC8013890.

- ICD-10-CM 2021: The Complete Official Codebook (ICD-10-CM the Complete Official Codebook). American Medical Association .2021.

- Lee J, Wachholtz A, Choi KH. A Review of the Korean Cultural Syndrome Hwa-Byung: Suggestions for Theory and Intervention. Asia Taepyongyang Sangdam Yongu. 2014 Jan;4(1):49. doi: 10.18401/2014.4.1.4. PMID: 25408922; PMCID: PMC4232959.

- Min SK. Hwabyung in Korea: Culture and dynamic analysis. World cultural psychiatry research review. 2009; 4(1): 12-21.

- American Psychiatric.Association A. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American psychiatric association. 2013.

- Ciesinski NK, Drabick DAG, McCloskey MS. A latent class analysis of intermittent explosive disorder symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2022 Apr 1;302:367-375. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.099. Epub 2022 Jan 29. PMID: 35101522.

- Coccaro EF, Lee R, Coussons-Read M. Elevated plasma inflammatory markers in individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and correlation with aggression in humans. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Feb;71(2):158-65. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3297. PMID: 24352431.

- Fettich KC, McCloskey MS, Look AE, Coccaro EF. Emotion regulation deficits in intermittent explosive disorder. Aggress Behav. 2015 Jan; 41(1):25-33. doi: 10.1002/ab.21566. PMID: 27539871.

- McCloskey MS, Berman ME, Noblett KL, Coccaro EF. Intermittent explosive disorder-integrated research diagnostic criteria: convergent and discriminant validity. J Psychiatr Res. 2006 Apr;40(3):231-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.07.004. Epub 2005 Sep 8. PMID: 16153657.

- McCloskey MS, Lee R, Berman ME, Noblett KL, Coccaro EF. The relationship between impulsive verbal aggression and intermittent explosive disorder. Aggress Behav. 2008 Jan-Feb;34(1):51-60. doi: 10.1002/ab.20216. PMID: 17654692.

- Coccaro EF, McCloskey MS. Phenomenology of impulsive aggression and intermittent explosive disorder. In Intermittent Explosive Disorder. 2019; 37-65. Academic Press.

- Ma J, Liu Y, Ma L, Huang S, Li H, You C. RNF213 polymorphism and Moyamoya disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol India. 2013 Jan-Feb; 61(1):35-9. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.107927. PMID: 23466837.

- Kessler RC, Coccaro EF, Fava M, Jaeger S, Jin R, Walters E. The prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;63(6):669-78. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.669. PMID: 16754840; PMCID: PMC1924721.

- Seo MK, Rhee MK. Mental health literacy and vulnerable group analysis of Korea. Korean Journal of Social Welfare 2013; 65:313-334.

- Ng CH. The stigma of mental illness in Asian cultures. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997 Jun;31(3):382-90. doi: 10.3109/00048679709073848. PMID: 9226084.

- Shea M, Yeh CJ. Asian American Students' cultural values, stigma, and relational self-construal: correlates of attitudes toward professional help-seeking. J Ment Health Couns. 2008; 30:157–72.

- Yang LH. Application of mental illness stigma theory to Chinese societies: synthesis and new directions. Singapore Med J. 2007 Nov;48(11):977-85. PMID: 17975685.

- Yang LH, Purdie-Vaughns V, Kotabe H, Link BG, Saw A, Wong G. Culture, threat, and mental illness stigma: identifying culture-specific threat among Chinese-American groups. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 88:56–67.

- Jang Y, Kim G, Hansen L, Chiriboga DA. Attitudes of older Korean Americans toward mental health services. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Apr;55(4):616-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01125.x. PMID: 17397442; PMCID: PMC1986774.

- Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Okazaki S. Attitudes toward mental health services: age-group differences in Korean American adults. Aging Ment Health. 2009 Jan;13(1):127-34. doi: 10.1080/13607860802591070. PMID: 19197698; PMCID: PMC2737391.

- Bonabi H, Müller M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Eisele J, Rodgers S, Seifritz E, Rössler W, Rüsch N. Mental Health Literacy, Attitudes to Help Seeking, and Perceived Need as Predictors of Mental Health Service Use: A Longitudinal Study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016 Apr;204(4):321-4. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000488. PMID: 27015396.

- Hur YM.Genetic and Environmental Influences on Hwabyung-Personality in South Korean Adolescents and Young Adults. Korean Journal of Stress Research. 2020;28(1), 25-32.

- Cox SJ, Mezulis AH, Hyde JS. The influence of child gender role and maternal feedback to child stress on the emergence of the gender difference in depressive rumination in adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2010 Jul;46(4):842-52. doi: 10.1037/a0019813. PMID: 20604606.

- Kingsbury MK, Coplan RJ. Mothers’ gender-role attitudes and their responses to young children’s hypothetical display of shy and aggressive behaviors. Sex roles. 2012; 66(7): 506-517.

- Park IJ, Kim PY, Cheung RY, Kim M. The role of culture, family processes, and anger regulation in Korean American adolescents’ adjustment problems. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(2): 258.

- Kwon HI, Lee SY, Kwon JH. Hwabyung symptoms and anger expression in relation to submissive behavior and external entrapment in a married couple. The Korean Journal of Woman Psychology.2012; 579-595.

- Kwon JH, Kim JW, Park DG, Lee MS, Min SK,Kwon HI, Development and validation of the Hwabyung scale. The Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology.2008; 237-252.

- Min SK, A study of the concept of Hwabyung. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc.1989; 604-616.

- Kim E, Hogge I, Ji P, Shim YR, Lothspeich C. Hwa-Byung among middle-aged Korean women: family relationships, gender-role attitudes, and self-esteem. Health Care Women Int. 2014 May;35(5):495-511. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.740114. Epub 2013 Apr 29. PMID: 23627346.

- Shin HS, Shin Ds. Korean women’s causal perceptions of Hwabyung. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2004; 10:283–90. doi: 10.4069/kjwhn.2004.10.4.283.

- Kim E, Seo J, Paik H, Sohn S. The Effectiveness of Adlerian Therapy for Hwa-Byung in Middle-Aged South Korean Women. The Counseling Psychologist. 2020; 48(8):1082-1108.

- Jang JM, Park JI, Oh KY, Lee KH, Kim MS, Yoon MS, Ko SH, Cho HC, Chung YC. Predictors of suicidal ideation in a community sample: roles of anger, self-esteem, and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2014 Apr 30;216(1):74-81. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.054. Epub 2014 Jan 9. PMID: 24507544.

- An S, Lee H. An Exploratory Study on How and Why Young and Middle-aged Adults Disclose Depressive Feelings to Others: Focusing on the Influence of Perception of Social Norms Journal of Korean Academy of Community Health Nursing. 2021; 32(1):12-23.