More Information

Submitted: July 06, 2022 | Approved: July 25, 2022 | Published: July 26, 2022

How to cite this article: Zouine M, Elbaz M, Elhoudzi J. Being a parent of a child with cancer: What psychosocial and family repercussions. Arch Psychiatr Ment Health. 2022; 6: 032-035.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001041

Copyright License: © 2022 Zouine M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Being a parent of a child with cancer: What psychosocial and family repercussions

M Zouine* , M Elbaz and J Elhoudzi

, M Elbaz and J Elhoudzi

Pediatric Oncology, Hematology Center, University Hospital Mohammed VI, Marrakech, Morocco

*Address for Correspondence: M Zouine, Pediatric Oncology, Hematology Center, University Hospital Mohammed VI, Marrakech, Morocco, Email: [email protected]

Cancer is a serious disease that affects deeply and painfully not only the child who has cancer but also their parents. Through this study, we describe the different aspects of the impact of pediatric cancer on parents: the psychological, social, and family impact to offer optimal care to these parents.

Results: mothers represent 82.5% of the participants in our survey. More than sixty percent were of urban origin. The average time from diagnosis to parents’ assessment was 7.3 months. This announcement was made by doctors in 87.5% of cases. Conscious denial of cancer when it was announced was reported in 75% of parents. The social impact of pediatric cancer on parents was significant. The child’s illness was experienced as a very significant psychological distress; all of the parents said they had given up on important projects after their children’s illness. The psycho-emotional impact was represented by feelings of guilt in 37.5% and incapacity for illness in 30%. Forty-two percent felt tensions on the marital level with significant repercussions on the couple with a type of destabilization in 60% of cases. The parent’s relationship with the rest of the family, especially siblings, was marked by neglect and anxiety in 35% and 26% respectively.

Conclusion: The discovery of pediatric cancer induces various feelings that will inevitably have an impact on the parents of the affected child. Understanding the different aspects of this impact on the parents’ psycho-social, emotional and family experiences will make it possible to offer optimal care.

Pediatric cancer is a rare disease, however, it is the second leading cause of infant mortality. Its development is more common among infants and children between one and four years of age than among those in early schooling. The most common cancers are leukemia (33%), tumors of the central nervous system (21%) and lymphoma (12%). During pediatric cancer, the child, initially, a source of pleasure and dreams for the parents, becomes a sign of failure. The future and the balance of the family are called into question, which impacts the whole family on different levels, particularly psychological but also intra-family. Numerous studies have examined the emotional, physical, and mental health impact of parents of children with cancer. They report high rates of emotional and mental impairment compared to the general population [1,2]. The objective of this work is to describe the psychosocial, emotional, and family impact of pediatric cancer and to identify the target parents for support and management strategies in order to prevent the development of emotional manifestations that disrupt the healing process of the child.

This is a survey carried out at the Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Center of the university hospital Mohammed VI in Marrakech over a period of 04 months (February to May 2021). The questionnaire was validated by our professors and discussed with a multidisciplinary staff. It was carried out with 40 parents whose children are being followed for cancer. The course of the study and its objectives were explained and oral consent was obtained. Participants in this study were contacted during a follow-up consultation. The interview took place, either before or after the consultation, in calm conditions. We considered it appropriate to select a single parent; the most involved in the medical care procedure for the smooth running of data collection. We developed a questionnaire comprising 41 items concerning the history of the disease, its announcement, and the information they received, as well as the impact of the disease on the social, somatic, psychological and family experience of the parents.

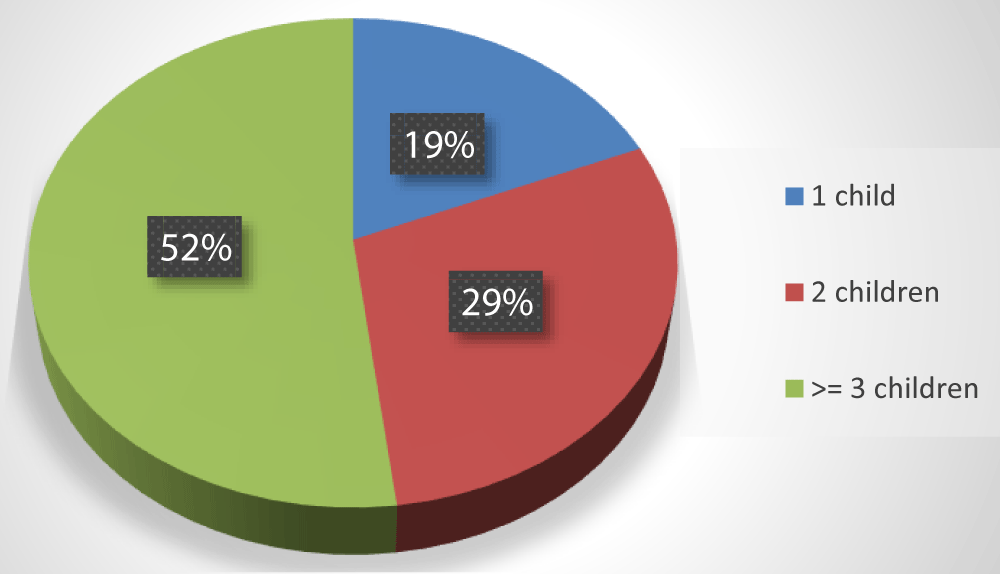

Most of the parents in our series were between 30-39 years old, often mothers in 82.5%, of urban origin in 62.5%, married in 87.5%, and more than 50% had three or more children. The characteristics of the parents are summarized in Table 1, Figure 1.

| Table 1: Socio-demographiccharacteristics of parents. | |

| Features | Number of parents (40) |

| Gender | |

|

33 (82.5%) |

|

07 (17.5%) |

| Marital Status | |

|

35 (87.5%) 03 (7.5%) 02 (5%) |

| Origin | |

|

15 (37.5%) |

|

25 (62.5%) |

| School Level | |

|

32 (80%) 04 (10%) 03 (7.5%) 01 (2.5%) |

Figure 1: Distribution of parents according to the number of children.

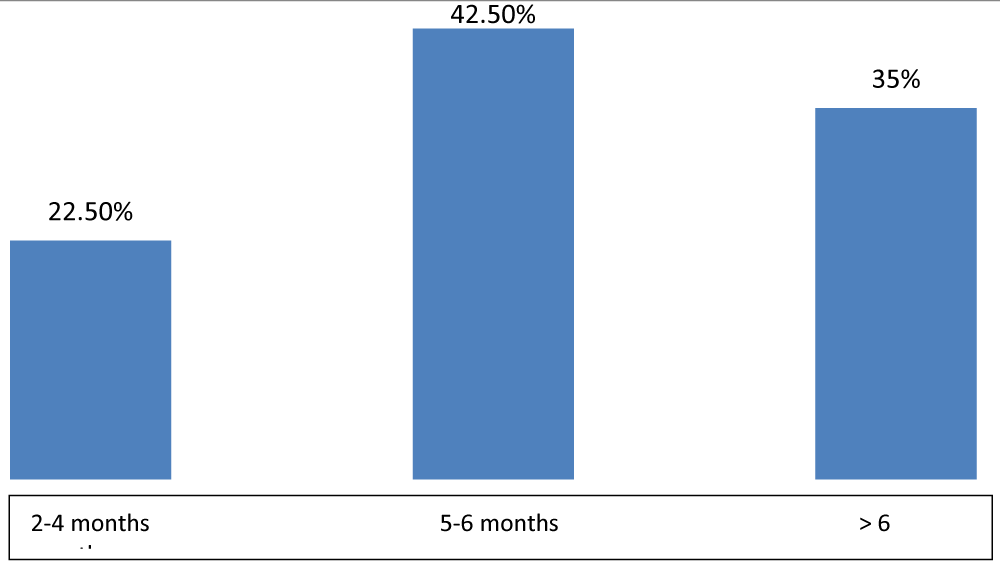

Concerning the clinical data of the children, the average age at the time of the diagnosis was 4.2 years ± 1.6, and the average time between the announcement of the diagnosis and the evaluation of the parents was 7.3 months ± 2.

Table 2 summarizes the types of cancer in our series. Seventeen parents or 42.5% knew the name of their children’s cancer. They saw the disease as being serious in 30% of cases. All parents remembered when the diagnosis was announced. The announcement was made by doctors in 87.5%, by nurses in 5% and 7.5% of parents had learned about it accidentally by reading the poster at the entrance to the service. After a phase of conscious denial of cancer when it was announced in 75%, most parents reported having gradually accepted it thereafter.

| Table 2: Distribution of children by type of cancer. | ||

| Type of the cancer | Effected | Percentage |

| ALL | 17 | 42.5% |

| Neuroblastoma | 6 | 15% |

| TLL | 5 | 12.5% |

| Nephroblastoma | 3 | 7.5% |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 | 7.5% |

| Ostéosarcoma | 2 | 5% |

| Renal sarcoma | 1 | 2.5% |

| Médulloblastoma | 1 | 2.5% |

| Maladie de Hodgkin | 1 | 2.5% |

| Hépatoblastoma | 1 | 2.5% |

| Total | 40 | 100% |

Concerning the repercussions of the child’s illness on the social experience, all the parents in our series felt that life after their child’s illness is very difficult despite the support and entourage of the family. Ninety percent report being well surrounded by their family after their children’s illness. The disease was not kept secret from those around them all of the participants in our survey.

All the parents all report having a good relationship with the hospital team. They all made new acquaintances at the hospital. For 80% of them, seeing cases as their children brought back a feeling of relief, but for 20% seeing other children suffer represented additional psychological distress. All of the parents claimed to have given up on important projects after their children’s illness. Twenty-two parents or 55% reported having no plans for the future of their child, healing was the main concern at the time of the interview Figure 2.

Figure 2: Time from Diagnosis to Parental Assessment.

The impact of the child’s illness on the parental somatic level was also present. Seventeen parents or 42.5% felt physically tired since their children’s illness. Frequent visits to consultations were involved in 62.5%, and food preparations in 20%. Sleep and appetite disorders were found respectively in 52.5% and 45% of cases. On the psychological level, the parents all experienced psychological suffering. They lamented having lost their positive outlook on life and felt more vulnerable to traumatic events. The feeling of guilt linked to the fantasy of being responsible for the disease of the loved one was present in 37.5%. This guilt was expressed most of the time by: “I had not insisted that my child consult at the appropriate time” or even “I didn’t have the means to provide my child with care as soon as the first symptoms appeared”. Feelings of incapacity and exhaustion predominated in 30% of them. None of the parents interviewed thought of stopping the consultations and follow-ups despite the constraints expressed. 37% claimed to need specialized psychological care. Concerning the impact of childhood cancer on the family system, 42.5% of parents felt tensions on the marital level with significant repercussions on the couple, such as destabilization in 60% of cases, while 20% felt that their couple became more close-knit after the child’s illness. All the parents were satisfied with the way their sick children got along with the rest of the family, especially with siblings. However, some parents felt that their relationship with the rest of the siblings was marked by neglect and anxiety 35% and 26% respectively.

Announcement of the disease

The first key moment for parents is the announcement of the diagnosis. For most parents, the announcement of the disease is a “violent, revolting, terrifying” moment [3]. Several emotions can emerge at this time, particularly the denial that was almost present among the majority of the parents in our series. The experiences were extreme and seemed to depend on the content of the ad, but also on how the message was conveyed. We note that in our series the announcement was made in 87.5% by doctors except in a few cases where the parents are referred from another structure or when reading the service poster. In the oncology department, we insist that the information be given gradually, at a pace that depends on the medical urgency and the understanding of the family. But as Saltel points out [4]: “There are no ‘right’ ways to deliver bad news, but some are more devastating than others”. The information must therefore be evaluated as it arises, according to the questions and needs of the parents and the child [5,6].

Psychological impact

Among all the parents interviewed, we often perceive a direct trauma due to the fear of death, pain, and sequelae. The feeling of incapacity was present in more than half of the parents we interviewed. However, none of them think of stopping the follow-up and the consultations despite the request for specialized psychological care. In other cases, the feeling of guilt was present, the parents reproached themselves for not having seen, or not understanding the case of their child from the beginning of the symptoms. As Dolphin et al. point out, parents can experience more or less intense depressive moments that sometimes have to be treated medically [7]. Other parents resign from their parental duties, leaving the child alone in reality. This resignation is particularly complex when the parents feel that their child is in great pain. Feeling helpless, bad, or useless, they may actually flee [3].

See other similar cases

During the child’s hospitalization, the parents are in contact with each other. In our series, although the majority of parents are relieved and supported by the presence of other parents “who have been there”, others saw this as another source of anxiety and concern. Indeed, it is often the children who have had complications who stay longer in the hospital, while those whose treatment is proceeding normally go home quickly [8-10]. Thus, intra-hospital contact can be a source of support, but also sometimes of discouragement or concern [10].

On the somatic level

On a somatic side, the diagnosis of cancer itself, but also the evolution of the disease can affect the level of parental health [11]. In the study by Wellish [12], sleep disorders are reported in 40% of cases, a decrease in appetite is reported in 26% of cases as well as disturbed work capacities (42%). Saltel [13] clearly shows “that the symptoms of stress (headaches, somatization) are more important in the parent than in the patient: only the fatigue of the patient is greater than that of his companion [11-13]. These data coincide with the results of our series where sleep and appetite disorders were the main disorders found in the parents.

Intrafamily relationships

The period of the child’s illness is often marked in the parents by significant psychological suffering with moments of doubt and depression [9]. In our series, many parents affirmed the existence of intramarital tensions since their child’s illness, was mainly linked to impaired communication and discouragement. Intramarital communication can disappear, become rare or become paradoxical. Difficulty communicating verbally is common in these situations where the future is uncertain and difficult to imagine [1,8]. The relationship with the rest of the family, particularly with siblings, risks being jeopardized because, during this entire period, the brothers and sisters of a sick child are often in pain. They live in great loneliness and are worried about him. They no longer benefit from parental presence as often as before and this increases the feeling of inevitable jealousy in them [9]. In Morocco and as in several other countries where the family is often large, the presence of people capable of taking over makes it possible to mitigate these repercussions and thus come to the aid of both the siblings and the parents of the sick child. This explains why all the parents in our series have good relations with the rest of the family and those around them.

The development of psycho-oncology within oncology departments will prevent the negative repercussions of the cancerous disease on the psyche of the child but also of those around him, particularly his parents. The establishment of listening cells dedicated to these parents will also help to relieve their psychological pain and provide psychosocial support. Without forgetting the important role that civil society can play in protecting families with a child suffering from cancer from financial ruin and social isolation linked to treatment through associations and solidarity actions.

This work was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles set out in the IRB & Declaration of Helsinki.

- Canada has public health. Leading causes of death, canada, 2008, males and females combined, number (death rate by age group per 100,000). AEM. 2008.

- Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, Frazier AL, Atun R. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Apr;20(4):483-493. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30909-4. Epub 2019 Feb 26. PMID: 30824204.

- Claire van Pevenage and Isabelle Lambotte. The family facing the seriously ill child: the psychologist's point of view. Families with seriously ill children: the psychologist's perspective.

- Saltel P. announcement of a disability, hear from parents seeking care. Interuniversity diploma in pediatric pain and palliative care, pdf of the slide show, 2010-2012 session. lyon 1 / clermont-ferrand 1 / nancy 1 / paris v / paris vi.

- Bétrémieux P, Gold F, Parat S, Farnoux C, Rajguru M, Boithiais C, Mahieu caputo D, Jouannic JM, Hubert P. The practical implementation of palliative care in the different places of care: 3rd part of reflections and proposals around palliative care in the neonatal period. Pediatric Archives. 2010; 420-425.

- Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ. Psychosocial functioning in pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005 Jan-Feb;30(1):9-27. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi012. PMID: 15610981.

- Dolgin MJ, Phipps S, Fairclough DL, Sahler OJ, Askins M, Noll RB, Butler RW, Varni JW, Katz ER. Trajectories of adjustment in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: a natural history investigation. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007 Aug;32(7):771-82. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm013. Epub 2007 Apr 2. PMID: 17403910.

- Thorne S. The family cancer experience. Cancer Nursing. 1985; 8(5): 285-291.

- Carter EA, Mcgoldrick M. the family life cycle: a framework for family therapy. Gardner press, new York

- Aregui C. My child has cancer: understanding and being helped 2014. National cancer institute.

- Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, Triemstra M, Spruijt RJ, van den Bos GA. Cancer and caregiving: the impact on the caregiver's health. Psychooncology. 1998 Jan-Feb;7(1):3-13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<3::AID-PON320>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID: 9516646.

- Wellisch DK, Jamison KR, Pasnau RO. Psychosocial aspects of mastectomy: II. the man's perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 1978 May;135(5):543-6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.135.5.543. PMID: 645946.

- Saltel P. psychological adaptation of loved ones to the disease, and how to approach end-of-life situations? In: psychological adaptation of relatives to the disease workshop, “cancer and relatives” forum, Paris, 10 December.