More Information

Submitted: 11 February 2020 | Approved: 27 February 2020 | Published: 28 February 2020

How to cite this article: Turabian JL. Transference and countertransference are linked to placebo-nocebo effects and they are an auxiliary resource of unparalleled value in general medicine: Recommendations for general practitioners. Arch Psychiatr Ment Health. 2020; 4: 001-006.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001010

ORCiD: 0000-0002-8463-171X

Copyright License: © 2020 Turabian JL. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Communication; Physician patient relations; Psychotherapeutic processes; Transference (Psychology); Countertransference (Psychology); Placebo effect; Nocebo effect

Transference and countertransference are linked to placebo-nocebo effects and they are an auxiliary resource of unparalleled value in general medicine: Recommendations for general practitioners

Jose Luis Turabian*

Specialist, Family and Community Medicine, Health Center Santa Maria de Benquerencia, Regional Health Service of Castilla la Mancha (SESCAM), Toledo, Spain

*Address for Correspondence: Jose Luis Turabian, Specialist, Family and Community Medicine, Health Center Santa Maria de Benquerencia. Regional Health Service of Castilla la Mancha (SESCAM), Toledo, Spain, Tel: 34925230104; Email: [email protected]

Psychological phenomena of the doctor-patient relationship influence the therapeutic process. Among these phenomena are the transference (the emotions of the patient towards the doctor), and the countertransference (the emotional reactions of the doctor towards the patient). Doctor and patient are within an interactive relationship in a conscious and unconscious way: the patient is influenced by the doctor, and vice versa. Doctor is solely responsible for the control of transference and countertransference, since patients do not have a conscious perception of these phenomena. In general medicine the transference/countertransference have connotations of placebo effect and nocebo. The challenge of the doctor-patient relationship for the doctor is to realize the transference and countertransference phenomena and use them to achieve placebo effects and minimize the nocebo, and also respecting the needs of both parties, so that to improve the quality of clinical practice. Under these conditions, transference and countertransference are auxiliary resources of unparalleled value.

The doctor-patient relationship is a complex phenomenon conformed by several aspects, among which we can point out the doctor-patient communication, the patient participation in decision-making and the patient satisfaction [1]. The transcendence of psychological factors of the doctor-patient relationship is given by the fact of its influence on results and quality of medical care, improvement in compliance, satisfaction and recall of physician information, and plays a fundamental role in the medical care process [2].

The doctor-patient relationships influence the therapeutic process. Good relationships favour the process: it is what is called a therapeutic relationship; in the opposite case, the relationship that harms the therapeutic process is iatrogenic. For the doctor-patient relationship to become therapeutic it is necessary to know the psychological phenomena that occur in that relationship. Although a good doctor-patient relationship cannot be expressed in numbers or reflected in health statistics, there is overwhelming evidence that it continues to largely determine the effectiveness of individual medical care [3,4].

Among the psychological phenomena that occur in the consultation, based on the doctor-patient relationship, we can mention:

1. Transference are the emotions of the patient towards the doctor (positive or negative feelings).

2. Countertransference are the emotional reactions of the doctor towards the patient, such as feelings (frustration) and behaviors (rudeness).

The understanding of these psychological phenomena is essential for an adequate professional relationship with patients. Consequently, when the doctor does not recognize this kind of response, they greatly affect his relationship with patients [5].

Despite the predominant biologic approach in medicine, many experts agree that there is currently an oversight in the care of symptoms and signs that are not in the first instance of “biological” lineage [6]. In consequence, factors may not be taken into account that are related to the biopsychosocial knowledge of the patient and the establishment of a peculiar relationship with him, such as the doctor-patient relationship. In this way, there is an insufficiency in strict biomedical models to conceptualize and manage the problems of medical care. C. Jung used the comparison between chemistry and alchemy (objective and subjective or symbolic and emotional) to refer to internal change or transformation in relation to the phenomenon of transference and treatment of patients. He highlighted the fact that “Everyone who has had practical experience of psychotherapy knows that the process which Freud called “transference” often presents a difficult problem. It is probably no exaggeration to say that almost all cases requiring lengthy treatment gravitate round the phenomenon of transference, and that the success or failure of the treatment appears to be bound up with it in a very fundamental way [7].

On the other hand, it is established that psychosocial factors give rise to biological changes. The extent that we respond emotionally to someone, we respond physiologically to that person. Consequently, people in an emotionally significant relationship share physiological responses associated with those emotions. The emotions of fear and pain that accompany patients’ symptoms so often are driving them to seek relief through medical care, an important ingredient of which is the doctor’s affective care. People in an empathic relationship exhibit a correlation with indicators of autonomic activity. This occurs between speakers and responsive listeners, members of a coherent group, and bonded pairs of higher social animals. Furthermore, the experience of feel cared about in a relationship reduces the secretion of stress hormones and shifts the neuroendocrine system toward homeostasis. Because the social engagement of emotions is simultaneously the social engagement of the physiologic substrate of those emotions, the process has been labelled sociophysiology. This process can influence the health of both parties in the doctor-patient relationship, and may be relevant to third parties [8].

Being optimistic builds rapport. It is the degree of affective contact between patient and therapist. The rapport includes the state of mutual trust and respect between the doctor and the patient. Rapport is related to the “therapeutic alliance” construct. Optimistic people convey confidence and a sense of power and make us want to be close to them [9].

For Balint, the most commonly used drug in general practice is the doctor himself. In his writings on “the doctor as a drug” he establishes the fact that he himself can dose, prescribe, and can poison as any drug. With relative frequency the relationship between the doctor and the patient is poor or tense; in these cases the “drug” does not achieve the expected results. This medicine called “doctor” is potent and can have many side effects. In the doctor-patient relationship there will be periods in which the patient prefers not to maintain contact, while there will be times when patient needs to have someone -the doctor- for complain about some problems in consultation; these lapses can alternate quickly or slowly, but we know little about the forces that govern them [10-12].

There are recovery mechanisms of the disease that are more complex than homeostasis. Among these is the placebo effect. They are true social, cultural and psychobiological responses that can significantly modify the overall outcome of the treatment. The effects of placebo and nocebo occur frequently and are clinically significant, but are not recognized despite the theoretical comprehensive framework of general medicine [13].

Consequently, it is necessary to give as much attention to the psychology of the patient as to the diagnosis in any disease if recovery is to be achieved. But, in addition, doctors have feelings, and these have a role in the consultation [14,15].

In this scenario, this article which is a personal view or opinion paper, aims to reflect, synthesize and conceptualize, based on a selected narrative review and the author’s experience, the psychological phenomena of transference and countertransference and its relation to placebo and nocebo effects in doctor-patient relationship, in general medicine level, and its practical implications.

Doctor-patient relationship

In the doctor-patient relationship there is a duality: observe and be observed. The doctor is not aware of the curiosity that arouses in patients; however, it is subject to observation and an “almost microscopic” analysis. The real information that the patient does not obtain is elaborated through fantasies according to the role that the doctor plays in the transference. The activity of the general practitioner (GP) is similar to that of the psychoanalyst, because it constructively applies cognitive abilities to understand the patient’s unconscious throughout the clinical history [16-18].

GPs also experience emotions in consultation, although most occasions do not perceive or identify different forms of verbal and body communication. Psychodynamically, the doctor and the patient interact consciously and unconsciously, they are two different personalities, with different stories, in a dynamic interaction. The sick go to the doctor, who represents an authority that they structure according to their needs and fantasies; they seek health, be treated, heard, recognized and be reciprocated in the trust they give to the doctor. Both the patient and the doctor are in an interactive relationship, so the patient is influenced by the doctor and vice versa (16). In the old preanalytic psychotherapy, the transference was already defined as “relationship.” This relationship forms the basis of therapeutic influence once the initial projections of the patient are broken [7].

Transference and countertransference

Freud, who was the first to recognize and describe this phenomenon, coined the term “transference neurosis.” This link is often of such intensity that we could almost speak of a “combination.” When two chemicals combine, both are altered. This is precisely what happens in the transference. Freud rightly acknowledged that this link is of the greatest therapeutic importance, since it results in a mixed mix of the doctor’s own mental health and the patient’s mismatch. In the Freudian technique, the doctor tries to avoid the transference as much as possible, which is sufficiently understandable from the human point of view, although in certain cases it can significantly affect the therapeutic effect. It is inevitable that the doctor will be influenced to some extent and even that his nervous health suffers. In fact, in any human relationship certain transference phenomena will almost always function as useful or disturbing factors [7].

Transference is a concept described by Freud as a “phenomenon characterized by unconscious redirection of feelings from one person to another” or “a whole series of psychological experiences revived, not as belonging in the past, but as applying to the person ... at the present moment.” The transference implies experiences and relationships of the past that affect those of the present. The feelings, attitudes and desires, originally linked to the important figures of their first years of life, are projected on other people, in this case at the doctor. For example, the transference of feelings towards someone: one’s parents, couple or children, or the repetition of patterns of feelings and behaviors with someone new. This transference is due to unconscious inferences drawn from previous experiences with similar individuals. The contents that enter the transference are, as a rule, originally projected on the parents or other family members, and may have symbolic contents of sexuality, will to power, etc. [19,20].

The transference is [21]:

- ”When my patient is sad, I also begin to feel sad”

- ”When my patient gets angry, me too”

- ”If I start feeling X, Y or Z, my patient may also feel X, Y or Z”

Literally the doctor “takes care” of his patient’s sufferings and shares them with him. For this reason, it runs a risk, since certain health problems “can be extremely contagious” if the doctor himself has a latent predisposition in that direction [7]. Only the order of the symbolic allows elucidating the transference, since the symbol is a transformer of psychic energy. The almost logical conclusion drawn from the transference projection is that it links us more to an archetypal idea, as if it were that of a divinity, than that which could support that of the royal father. A priori, there is no reason that prevents unconscious tendencies from having an objective beyond the human person, that is, at symbolic levels such as those already mentioned [7,22].

Transference is an instinctive process and in part it is very difficult to interpret and classify. The instincts and their specific fantasy content are partly concrete, but partly symbolic (that is, “unreal”). The transference is far from being a simple phenomenon with only one meaning, and we can never understand in advance what it is. An unconscious link of the patient’s fantasies is established in the doctor. It is not too easy for the doctor to realize this fact. Naturally, one is reluctant to admit that any patient could affect him in the most personal way. But the more unconsciously this happens, this lack of knowledge will be a bad counsellor, since “unconscious contagion” (the transference) brings with it the therapeutic possibility that should not be underestimated [7].

Freud distinguished two types of transference, one positive, when feelings of tenderness appear, and another negative, when feelings of hostility emerge. Both the transference positive and negative (although classically it is said that doctors must recognize these forms of relationship but not get involved in them) in the hands of the doctor they become the most powerful of the therapeutic instruments and play an important role in healing process [16]. As the doctor has the expert power (‘authority’), the patient reacts in different ways when he or she cannot release the control over the diagnostic situation. Patient regressive power can be exercised in three forms of transference relationships: the power of dependency, the power of dominance and the power of disorganization [23,24].

Transference to medication can provide important information about specific ego dysfunction in sicker patients who often need medication. Whether positive or negative or both in content, the organization of the experience provides data of the illness ‘effect on the patients’ ego and can therefore be a specific diagnostic assessment strategy. Early resistances to medication may reveal the nature of resistances to the therapeutic alliance and to higher-level ego function. Understanding this can guide verbal and pharmacological interventions to strengthen ego function. Countertransference can similarly be helpful because it, too, can be a highly specific diagnostic indicator [25].

So, a related concept to transference, countertransference is the “redirection of a therapist’s feelings towards a patient.” Freud described countertransference as an act that arises in the doctor because of the influence that the patient exerts on his unconscious feeling. For some authors, countertransference it includes the capacity for empathy, dislike, sympathy and other affections, the mental functioning of the doctor, his failures, conflicts and problems. Freud considered it negative and as a process to be completely mastered by doctor, to later understand it as a necessary therapeutic tool for understands the transference processes of the patient. Countertransference is the spontaneous reaction of the doctor to the patient’s personality; this process is resolved in unconscious formations, which reach expression in the doctor’s attitude, an attitude that in turn produces changes in the transference of the patient [16,26].

It is important to remember that in any doctor-patient relationship an unconscious transference-countertransferential process is established that influences the management that the doctor gives to his patients. If the doctor does not find an organic cause to the symptomatology of his patient, he can react, among other things with disinterest, discomfort or insecurity, feelings that are likely to generate unconscious attitudes of rejection with the consequent difficulty to engage in a dialogue that clarifies the problem psychological of the person who consults it [27].

The doctor-patient relationship is a “combination.” When two bodies “combine”, a metaphor related to the therapeutic field, not only the patient is involved, but also the therapist. This last aspect should be understood as a kind of transformation that is taking place between both protagonists. In other words, the therapeutic field must be fluid and not at all rigid, the doctor being someone who tries to listen and say something on the same level as his patient, that of existence. A healthy and logical derivation of an approach like the one we have been pointing out is the appearance of the so-called countertransference. For Freud, the appearance of countertransference was an obstacle, a kind of resistance coming from the same analyst, so he considered it negatively; However, the opposite is true from the perspective of analytical psychology and in general medicine level of care. When there is necessarily a reciprocal influence between the doctor and his patient, both are facing a dynamic and permanent process. It is not uncommon then, the appearance of ideas or thoughts in the GP that are directly related to your listening. Moreover, doctor should not rule out without being previously investigated, the appearance of some intuitive phenomenology in him, since can be signaling paths to reach a better clinical understanding [17,18,22].

The role of expectations

Medical treatments typically occur in the context of a social interaction between healthcare providers and patients. Decades of research have demonstrated that patients ’expectations can dramatically affect treatment outcomes. And also, patients ’subjective experiences (for example, of pain) are directly modulated by healthcare providers’ expectations of treatment success [27].

The expectations we have about a patient modify their results and finally confirm our expectations. If we expect that a patient to be a difficult patient will be more likely he to be: our own behavior, attitudes, and verbal and non-verbal communication, consciously and unconsciously, will favour him. When we begin to think more positively about a patient, things are going better. Of course we are not obliged to like all patients, but if we control our assumptions and expectations we may be able to use them advantageously on ourselves and our patients [6,28].

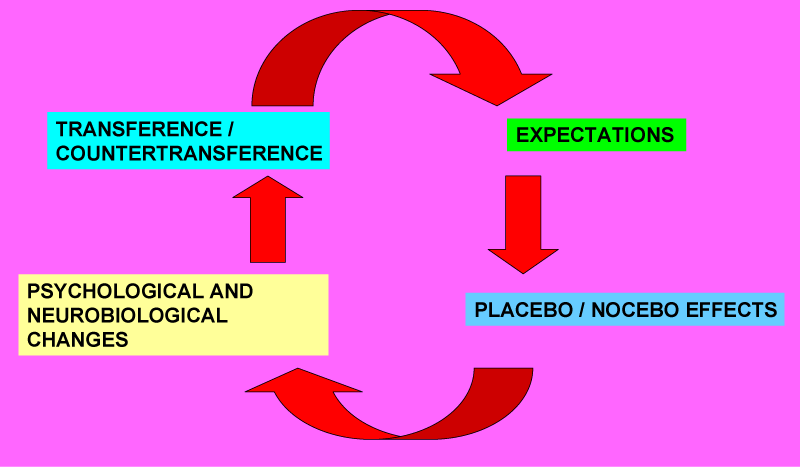

The placebo and nocebo effects are linked to the transference and countertransference phenomena (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The placebo and nocebo effects are linked to the transference and countertransference phenomena.

Basically, the placebo effect occurs when a person thinks that a certain intervention has generated effects when in fact the effects have not changed. In reality they remain the same, but what has changed is their perception. This effect has been studied especially in medicine, with medications and subjective pain. Placebo and nocebo effects occur in clinical or laboratory medical contexts after administration of an inert treatment or as part of active treatments and are due to psychobiological mechanisms such as expectations of the patient. There is consensus that maximizing placebo effects and minimizing nocebo effects should lead to better treatment outcomes with fewer side effects [6].

Placebos are “any therapeutic procedure (or a component of the therapeutic procedure) that is deliberately given to have an effect, or that unknowingly has an effect on the patient’s symptoms or illness, but that objectively does not have a specific activity for the treated condition.” The placebo effect is real and in some cases very substantial, and this effect is generally mediated by expectation [29].

Even when there is a true pharmacological effect of the prescribed active drug, it should be expected that its effect will be modified considerably by the optimism or confidence expressed by the doctor before the treatment. The results of the treatments are more dependent on the personality of the therapist than on the pharmacological effect or the technique used. There is evidence that health professionals can influence patients about the way they think and feel about their illnesses or their treatment. Therefore, the “how” of prescribing is than important as what it is prescribed [30].

So, not surprisingly, a pharmacological prescription whose decision is expressed by the doctor with great security, generally has a placebo effect; On the other hand, if the decision is considered to have a dubious effect, it will often give rise, depending on the general context of the consultation and the personality characteristics of the patient, to a nocebo effect, with deficient therapeutic results or adverse pharmacological. And we must remember that these effects are not mediated by the drug, but psychosocially. It has also been shown that the nocebo effect plays a role in introducing a new drug or in changing an established medicine, for example, by switching patients from a reference biological product to a biosimilar, which has repercussions on both the medical- patient relationship and in the healthcare costs [13,28].

The relationship of trust may be sufficient to improve symptoms of stress or anxiety, so that the effect attributed to any prescribed medication may be due to that relationship. It is about “the effect of the doctor himself as a drug”. The medicine most frequently used by GPs is the doctor himself. Consequently, the doctor himself should be considered as a drug, that is, that the concepts of pharmacology, such as overdoses, allergic reactions, side effects, etc., can be applied to the interaction between doctor and patient. Both, doctor and patient, are modified: one towards the other and vice versa [10-12,31].

Neurobiological explanations for the placebo effect have been uncovered in recent years, and there is a growing interest in understanding and harnessing it within the consultation - where the placebo effect is known as the context-mediated effect [32]. Placebo effects rely on complex neurobiologic mechanisms involving, among other pathways, neurotransmitters (eg, endorphins, cannabinoids, and dopamine) and activation of specific, quantifiable, and relevant areas of the brain (eg, prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, anterior rostral cingulate cortex, and amygdala in placebo analgesia) [13,33].

So, placebo does not act purely by suggestion. The placebo effect is not only a psychological effect or something that depends solely on our attitude or our perception. Placebo and nocebo effects are psychobiological events imputable to the therapeutic context. Their major mechanisms are expectancy and classical conditioning. Placebo and nocebo represent complex and distinct psycho neurobiological phenomena in which behavioral and neurophysiologic modifications occur together with the application of a treatment [34,35].

Patients treated at general medicine have emotional characteristics and personality traits, whose knowledge may allow identifying which of them, will have a placebo response and which of them a nocebo response in relation to prescription drugs. Furthermore, the presence of multidrug adverse reactions in the patient is an indicator that suggests the existence of emotional characteristics (anxiety and depression), negative personality traits, or contextual psychosocial problems. The GP should know the characteristics of their patients to maximize the placebo effect and minimize the nocebo, and investigate the emotional and contextual problematic in cases of patients with nocebo effects [36,37].

Projections (transference and countertransference) can also obscure the doctor’s judgment, even only to a small extent, of course, since otherwise all therapy would be impossible. Although, we can justifiably expect that doctor knows, at least, the effects of the unconscious on his own person. The only way in practice is to try to achieve a conscious attitude that allows the unconscious to cooperate instead of being led to opposition [7].

On the other hand, most references to the phenomena of transference and countertransference refer to the scope of psychoanalyst practice. Consequently, it is necessary to review these concepts, which define the field of the analyst relationship, but whose application to the field of general medicine and the doctor-patient relationship cannot be done linearly. We must take into account contextual and social aspects that are broader than the individual psychological vision. The transference must be taken not only as a link addressed to an individual, but also to a healthcare institution, that is, that the user has a representation of the doctors, the team, and the institution to which he demands. In turn, the countertransference is loaded with elements of the professional’s involvement in the institution, such as the characteristics of its insertion or certain tensions or conflicts that may exist at that time in institutional dynamics [22].

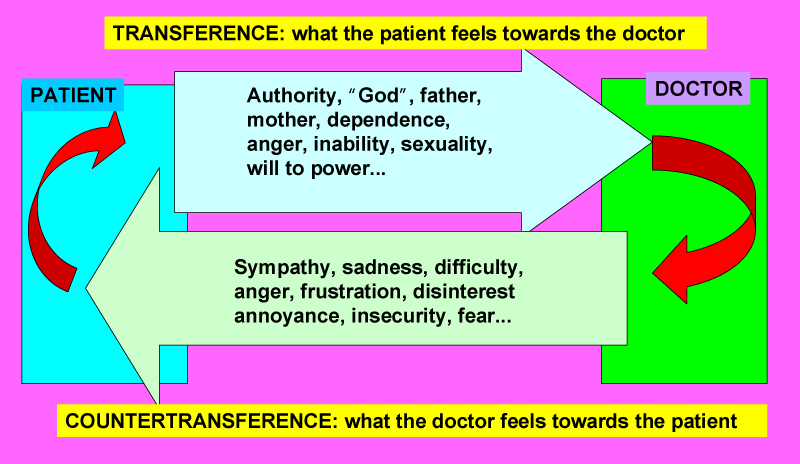

Doctor and patient are in a relationship founded, initially, on mutual unconsciousness. The GP is solely responsible for the control of transference and countertransference, as patients do not have a conscious perception of these phenomena. The GP must learn to know and manage this “relational dimension”, where subjective experiences are. The effects of placebo and nocebo occur frequently and are clinically significant, but are not recognized in clinical practice. Patient expectations are important determinants of the success of a treatment or, conversely, of unwanted adverse effects. In general medicine the transference has connotations of placebo effect and nocebo. The psychodynamic concepts of transference and countertransference can be used to help understand and manage the placebo and nocebo effects that arise within the doctor-patient relationship. The GP has to identify and use their emotions during the consultation for the benefit of the patient. The challenge of the doctor-patient relationship for the doctor is to realize the transference and countertransference phenomena and use them to achieve placebo effects and minimize the nocebo, and also respecting the needs of both parties, so that to improve the quality of clinical practice (Figure 2). Under these conditions, transference and countertransference are auxiliary resources of unparalleled value. It is important teaching and training doctors about placebo and nocebo effects in patient-doctor metacommunication to be trained to maximize placebo and minimize nocebo effects. Consequently, GPs must combine active medication with a specific context and an adequate level of therapeutic contact, to improve non-specific effects of treatment and obtain a greater response to treatment.

Figure 2: Doctor must be aware of the transference and countertransference phenomena and use them to achieve placebo effects and minimize nocebo effects

- Turabian JL. Doctor-Patient Relationship as Dancing a Dance. Journal of Family Medicine. 2018; 1: 1-6.

- Turabian JL. Psychology of doctor-patient relationship in general medicine. Arch Community Med Public Health. 2019; 5: 062-068.

- Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002; 15: 25-38. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11841136

- Matusitz J, Spear J. Effective doctor-patient communication: an updated examination. Soc Work Public Health. 2014; 29: 252-266. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24802220

- Reyes Ortiz CA, Gheorghiu S, Mulligan T. Forgetting psychological phenomena in the elderly doctor-patient relationship. Colombia Médica. 1998; 29.

- Evers AWM, Colloca L, Blease C, Annoni M, Atlas LY, et al. Implications of Placebo and Nocebo Effects for Clinical Practice: Expert Consensus. Psychother Psychosom. 2018; 87: 204-210. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29895014

- Jung CG. The practice of psychotherapy. Essays on the psychology of the transference and other subjects. New York: Bollingen Foundation Inc. 1954.

- Adler HM. The Sociophysiology of Caring in the Doctor-patient Relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2002; 17: 874-881. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12406360

- Strachey J. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XII (1911-1913): The Case of Schreber, Papers on Technique and Other Works. ii-vii. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis, London. 1958.

- Balint M, Hunt J, Joyce D, Marinker M, Woodcock J. Treatment or diagnosis. A study of repeat prescriptions in general practice. London: Tavistock Publications. 1984.

- Turabián Fernández JL, Pérez Franco B. The concept of treatment in familiy medicine: A contextualised and contextual map of a city hardly seen. Aten Primaria .2010; 42: 253-254. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20207448

- Turabian JL. Doctor-Patient Relationship in Pharmacological Treatment: Discontinuation and Adherence. COJ & Res. 2018; 1.

- Turabian JL. The placebo effect from the biopsychosocial perspective of general medicine: non-effective interventions that are, in fact, effective. Int J Fam Commun Med. 2019; 3: 16-21.

- Cousins N. Anatomy of an illness as perceived by the patient. Reflections on healing and regeneration. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1979.

- Van Roy K, Vanheule S, Debaere V, Inslegers R, Meganck R, et al. A Lacanian view on Balint group meetings: a qualitative analysis of two case presentations. BMC Family Practice. 2014; 15: 49. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24655833

- Urbina-Méndez R, Hernández-Vargas CI, Hernández-Torres I, Fernández-Ortega MA, Irigoyen-Coria A. Psychodynamic Analysis of Transference and Countertransference in the Formation of Family Physicians in Mexico. Aten Fam. 2015; 22: 58-61.

- Turabian JL. Interpretation of the Reasons for Consultation: Manifest and Latent Content. the Initiation of the Diagnostic Process in General Medicine. Archives of Community and Family Medicine. 2019; 2.

- Turabian JL. Symptomatic Acts. A Type of Guidance Signs Not to Get Lost in the Forest of the Clinic in General Medicine. Presentation and Conceptualization from Two Cases. J Case Rep Med Spec. 2019; 1-10.

- Zinn WM. Transference phenomena in medical practice: being whom the patient needs. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 113: 293-298. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2375565

- Freedman N, Lasky R, Webster J. The ordinary and the extraordinary countertransference. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2009; 57: 303-331. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19516054

- McNally PJ, Charlton R, Ratnapalan M, Dambha-Miller H. Empathy, transference and compassion. JR Soc Med. 2019; 112: 420-423. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31609173

- Suárez F. Around the idea of "situation diagnosis". 2006.

- Van Marle HJ. The patient rules; the power of transference in the doctor-patient relationship. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2016; 160: D1219. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28000579

- Goldberg PE. The physician-patient relationship: three psichodinamic Concepts that can be applied to primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000; 9: 1164-1168. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11115224

- Marcus ER. Transference and countertransference to medication and its implications for ego function. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2007; 35: 211-218. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17650974

- Cooper SH. An elusive aspect of the analyst's relationship to transference. Psychoanal Q. 2010; 79: 349-380. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20496836

- Sánchez MA. Thought disorders and psychosomatic diseases. Revista Medicina. 2006; 28: 161-179.

- Chen PA, Cheong JH, Jolly E, Hirsh Elhence, Wager TD, et al. Socially transmitted placebo effects. Nat Hum Behav. 2019; 3: 1295-1305. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31636406

- Deligianni C, Mitsikostas DD. Nocebo in Headache Treatment. In: Mitsikostas D., Benedetti F. (eds) Placebos and Nocebos in Headaches. Headache. Springer, Cham. 2019.

- Kirsch I. Placebo psychotherapy: synonym or oxymoron? J Clin Psychol. 2005; 61: 791-803.

- Luban-Plozza B. Psychological aspects of drugs. Soz Praventivmed. 1980; 25: 56-60.

- Balint E, Norell JS. Six minutes for the patient: interactions in general practice consultations. London: Tavistock Publications. 1973.

- Nolan T. The placebo effect in general practice. InnovAiT. 2019.

- Mitsikostas DD, Deligianni CI. Placebo and Nocebo Effects. In: Mitsikostas D., Paemeleire K. (eds) Pharmacological Management of Headaches. Headache. Springer, Cham. 2016.

- Chavarria V, Vian J, Pereira C, Data-Franco J, Fernandes BS, et al. The Placebo and Nocebo Phenomena: Their Clinical Management and Impact on Treatment Outcomes. Clin Ther. 2017; 39: 477-486. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28237673

- Testa M, Rossettini G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: How contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Man Ther. 2016; 24: 65-74. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27133031

- Turabian JL, Moreno-Ruiz S. The fable of the pine and the palm tree: the two extremes. Strategies to maximize the placebo effect and minimize the nocebo effect in primary health care. Ment Health Addict Res. 2016; 1: 44-46.