Research Article

Comparison of Cardiovascular Risks following Smoking Cessation Treatments Using Varenicline vs. NRT among Schizophrenic Smokers

I-Hsuan Wu1, Hua Chen1, Patrick Bordnick2, Ekere James Essien1 Michael Johnson1, Ronald J Peters3 and Susan Abughosh1*

1Department of Pharmaceutical Health Outcomes and Policy, College of Pharmacy, University of Houston 1441 Moursund St, Houston, TX, 77030, USA

2University of Houston, Graduate College of Social Work, 4800 Calhoun Road, Houston, TX, 77004, USA

3University of Texas Health Center at Houston, School of Public Health, 7000 Fannin, Suite UCT 2618, Houston, TX 77030, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Susan Abughosh, Department of Pharmaceutical Health Outcomes and Policy, College of Pharmacy, University of Houston 1441 Moursund St, Houston, TX, 77030, USA, Tel: 832-842-8395, Fax: 832-842-8383, Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 14 October 2017; Approved: 18 October 2017; Published: 19 October 2017

How to cite this article: Wu IH, Chen H, Bordnick P, Essien EJ, Johnson M, et al. Comparison of Cardiovascular Risks following Smoking Cessation Treatments Using Varenicline vs. NRT among Schizophrenic Smokers. Arch Psychiatr Ment Health. 2017; 1: 001-010. DOI: 10.29328/journal.apmh.1001001

Copyright License: © 2017 Wu IH, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: Schizophrenic patients have a lot higher smoking rates when compared to people in the general population. A variety of pharmaceutical cessation aids are available, which include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), Bupropion SR, and Varenicline. Our objective was to assess which cessation medication would have lower risks in developing risk factors of cardiovascular diseases.

Methods: A population-based retrospective cohort study was conducted using the General Electric (GE) electronic medical record database (1995-2011). The cohort consisted of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (ICD-9 code 295.00-295.99) and who had newly initiated use of any smoking cessation medication. We excluded our cohort who (1) were not prescribed atypical antipsychotics and (2) already had diagnosis of diabetes, hyperlipidemia or hypertension prior to index date. Follow up period was from 12 weeks onwards index date up to one year. The hazard ratio of developing cardiovascular risks was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression model after controlling for other covariates.

Results: A total of 580 patients were included in our cohort. Among those, nearly half (n=276, 47.59%) developed one or more criteria of the metabolic syndromes. We found that smokers who were prescribed NRT were less likely to develop metabolic syndromes as compared to those who were prescribed Varenicline.

Conclusions: Physicians are advised to carefully weigh the risks against the benefits before prescribing cessation medications since risks for metabolic syndromes were found to be very high. Healthcare providers should monitor patients’ lab data regularly as this minority population is under higher risks.

Introduction

Schizophrenic patients have a lot higher smoking prevalence as compared to the general population: 72% - 90% vs. 23% [1]. Previous studies have also shown they tend to be heavy smokers [2], to have higher dependence level and much lower cessation rates [3,4]. The high prevalence can be possibly due to self-medication effect as tobacco may be used to alleviate some of the symptoms in schizophrenia [5,6].

The available cessation pharmacotherapies include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), Bupropion SR, and the most recent approved Varenicline [7,8]. Bupropion was originally approved by the FDA for treating depression under brand name Wellbutrin® in 1996 [9]. In the following year, FDA approved the same ingredients but under trade name Zyban® for smoking cessation [3]. The FDA suggested dosage regimen is usually for 12 weeks for cessation pharmacotherapies [10].

Cardiovascular disease is an important cause of morbidity and mortality among tobacco users. The long-term cardiovascular benefits of smoking cessation are well established [11,12]. However, weight gain after quitting is commonly cited [13]. The average weight gain in people who sustained quitting for eight years was about 9kg. This weight gain can have health consequences, with the incidence of diabetes and hypertension being higher in smokers that quit smoking than those who continue with the habit [14-17].

This weight gain would be a bigger concern for schizophrenic patients as the antipsychotic medications they take also increase their risk of metabolic syndromes especially for second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) [18,19]. With the weight gain from smoking cessation and SGAs combined, risks of developing metabolic syndromes have to be evaluated.

Furthermore, different cessation medications have their own problems: NRT has shown to reduce sensitivity to insulin and may aggravate or precipitate diabetes [20]. Bupropion has been shown to inhibit enzyme CYP2D6, the enzyme metabolizes antipsychotics, and increases risks of developing metabolic side effects. [21]. From a systematic review, Varenicline was associated with a significantly increased risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events compared with placebo [11]. Varenicline label was even updated as requested by FDA in December, 2012: “Post marketing reports of myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accidents including ischemic and hemorrhagic events have been reported [11].”

Our objective was to assess which cessation medication exposure would have lower risks in developing risk factors of cardiovascular diseases. This study is crucial as there is a need to evaluate how different smoking cessation strategies can modify these risks given the medication regimens schizophrenic patients already take.

Methods

Data source

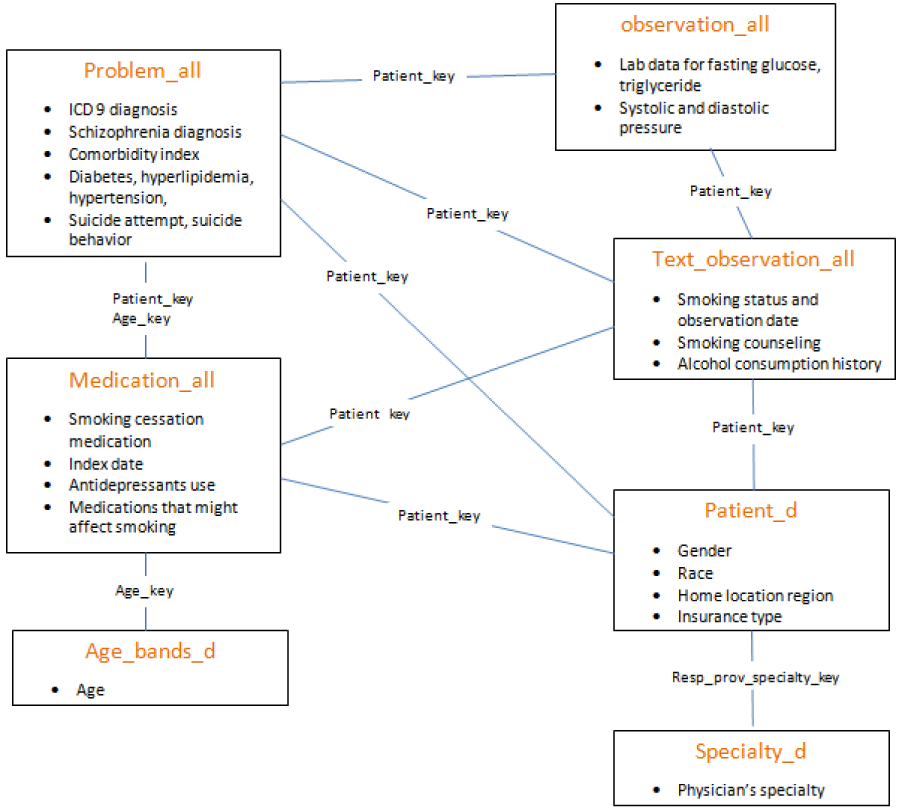

The data used for this study were extracted from the General Electric Centricity Electronic Medical Record (GE EMR) database. The Centricity EMR database is used by more than 20,000 clinicians and contains longitudinal ambulatory electronic health data for more than 7.4 million patients, including demographics, vital signs, laboratory results, medication list entries, prescriptions, and diagnoses. What made GE EMR an appropriate tool for our analysis is that some forms of NRTs are OTCs and could not be captured in claims data. The protocol to linking the different files is detailed in figure 1.

Study population

We included patients who were enrolled between 12/13/1995 to 10/31/2011. Patients aged less than 18 years old or those who received Wellbutrin® (Bupropion SR) for depression 6 months prior to index date were excluded. We identified patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (ICD-9 code 295.00-295.99) [22].

Numerous studies linked SGAs and not traditional antipsychotics to the development of metabolic syndromes in patients with schizophrenia [23], therefore, we only included those who had exposure of SGAs 6 months prior to index date in this cohort. Patient who already had diagnosis of diabetes, hyperlipidemia or hypertension prior to index date and who was prescribed more than one medication the same day as their index medication were excluded from the cohort.

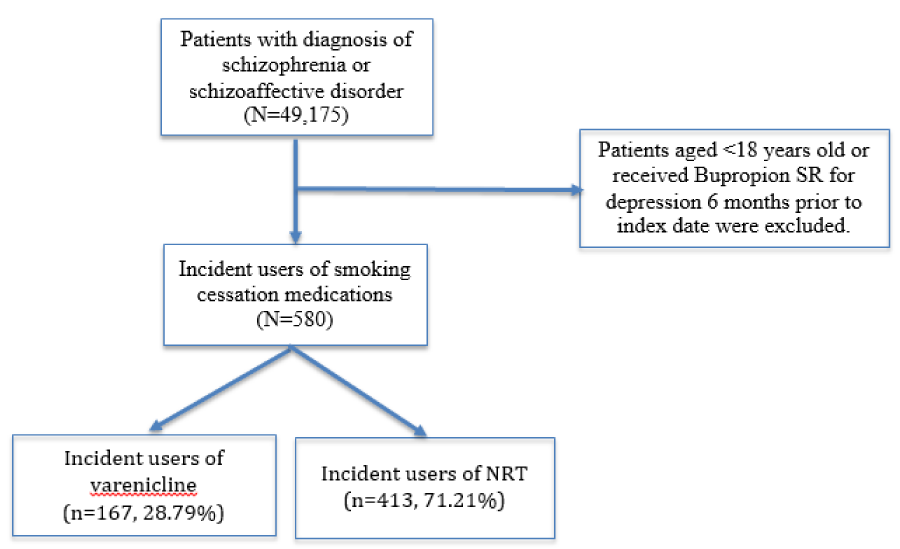

After identifying the population, we constructed a series of new-user cohort of patients who had newly initiated using smoking cessation medications. Only the first exposure (the first smoking cessation medication being prescribed during the study period) to each of the smoking cessation medication was examined so we could be sure the development of cardiovascular risks is not affected by the previous cessation product they took. The first day of being prescribed smoking cessation medication was defined as the index date. Cohort selection was presented in figure 2.

Definitions of outcome - cardiovascular risks (elevated glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure)

Cardiovascular disease is a long term outcome. Based on the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), some identified risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease include: (1) elevated fasting glucose (≧110 mg/dl), (2) elevated triglycerides (≧150 mg/dl), and (3) elevated blood pressure level (≧130/ ≧85 mm Hg) [24]. These metabolic syndromes can be assessed in a short term study. Previous cessation study requested participants come back for blood tests at week 12 and 52 [25]. Therefore, in our study, we examined patients’ diagnoses, medications, and their lab results 12 weeks onwards index date up to one year. Patients were considered to have elevated glucose level if they have an ICD9 code 250 [26] or received an anti-diabetic agent or with fasting glucose blood test results ≧ 110 mg/dL [24,27]. Similarly, the elevation of cholesterol level were identified by an ICD9 code 272 [28] or received an anti-hyperlipidemia agent [23], or with a triglyceride level ≧150 mg/dl [24,29]. On the other hand, the elevation of blood pressure was identified only by ICD9 codes 401 – 405 [26] or by blood pressure level ≧ 130/85 mmHg [24]. A prescription for antihypertensive was not considered as a reliable indicator because of the large number of secondary indications for these agents [23].

Statistical Analyses

Observation began 12 weeks after index day and continued until one year after the treatment exposure. At the end of one year window, patients would either develop the outcome or be censored. They were censored if they satisfied any of the three conditions below: (1) the last day of index medication being prescribed, (2) switching over to (or adding on) another smoking cessation medication and (3) did not develop the outcome when they reached the one year follow up timeline. We first carried out descriptive statistics and chi-sq analyses to examine the associations between patients’ characteristics and the outcome. A Cox proportional hazards model were then constructed and we studied the factors associated with elevated glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure level developed over the course of follow-up.

The primary outcome of interest in this Cox regression model was the cessation medication they received. Other potential confounders were included in Cox proportional hazards model as well, which included: age, race, gender, region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West), BMI (normal, over-weight or obese) [30], payment type (government or non-government insurance), specialty group (primary care, specialty care), nicotine addiction level, received smoking counseling, exposure to medications that might affect their smoking status (nortriptyline, buspirone, clonidine, naltrexone, mecamylamine, or rimonabant) and severity of mental disorder (having antipsychotic injections anytime one year before index date). Physical activities, diet, and family history of diabetes/hyperlipidemia/hypertension were not recorded in the data so those could be possible unmeasured confounding factors.

We tested proportional hazard assumptions using Schoenfield test. Variables with p<0.2 in univariate Cox regression analysis were included in the multivariate Cox regression model. Demographic variables like age, gender or race were included in the multivariate model regardless of the significance levels in the univariate analysis. Hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% CI were used to present the results for the final Cox PH regression model. Interaction terms between the main predictor and other independent variables were tested as well.

Results

Cohort distribution

From the inception of GE data, we found 49,175 patients had at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. About 10% of them got at least one cessation medication at any point. After applying more exclusion criteria, our cohort came down to a total of 580 patients. Please see Table 1 for detailed characteristics.

| Table 1: Overall cohort frequency and numbers in developing elevated glucose/cholesterol/blood pressure during 1-year follow up. | |||

| Characteristics | Overall cohort Frequency (%) |

Elevated glucose/cholesterol/blood pressure (n=276, 47.59%) | |

| Number (%) | Hazard ratio p-values |

||

| Demographics | |||

| Sex Female Male |

273 (47.07) 307 (52.93) |

117 (42.86) 159 (51.79) |

0.0186* |

| Age (years) | 0.7996 | ||

| Race Blacks Whites All others |

74 (12.76) 238 (41.03) 268 (46.21) |

32 (43.24) 120 (50.42) 124 (46.27) |

0.4721 |

| Region Midwest Northeast South West |

191 (32.93) 190 (32.76) 90 (15.52) 109 (18.79) |

93 (48.95) 94 (49.47) 41 (45.56) 47 (43.12) |

0.6242 |

| BMI Normal (BMI<25) Overweight (25<=BMI<30) Obesity (BMI>=30) |

255 (43.97) 123 (21.21) 202 (34.83) |

109 (42.75) 54 (43.90) 113 (55.94) |

0.0070* |

| Insurance Not Medicare/Medicaid Medicare or Medicaid |

272 (48.75) 286 (51.25) |

125 (45.96) 141 (49.30) |

0.3764 |

| Clinical factors | |||

| Comorbidty Index | 0.0007* | ||

| Had antipsychotic injectables 1 year prior to index date No Yes |

556 (95.86) 24 (4.14) |

268 (48.20) 8 (33.33) |

0.1565* |

| Smoking Cessation Related | |||

| Addicted to nicotine (# of cigarettes smoked per day ≥1) No Yes |

103 (17.76) 477 (82.24) |

44 (42.72) 232 (48.64) |

0.3965 |

| Cessation Medication Varenicline NRT |

167 (28.79) 413 (71.21) |

90 (53.89) 186 (45.04) |

0.0837* |

| Cessation Rx given by specialty care physician? No Yes |

562 (96.90) 18 (3.10) |

270 (48.04) 6 (33.33) |

0.2499 |

| Received any medication that might affect smoking status anytime 1 year prior to index date No Yes |

541 (93.28) 39 (6.72) |

262 (48.43) 14 (35.90) |

0.2049 |

| Smoking counseling received anytime one year prior to index date No Yes |

349 (60.17) 231 (39.83) |

169 (48.42) 107 (46.32) |

0.6290 |

| Total cohort=580; * p≤0.05 | |||

Slightly more than half were of male gender (n=307, 52.93%), about forty percent were whites (n=238, 41.03%), and majority were with high nicotine addiction level (n=477, 82.24%). About half of the cohort (n=255, 43.97%) had a normal BMI as they did not have the diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia. Almost all of them had stable mental states as only 4.14% (n=24) of the cohort had antipsychotics in the injection form at any point 1 year prior to index date. The mean age of the cohort was 40.56 years old (± SD: 11.68). We did not include Bupropion because we only had 10 individuals after applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria. This sample size was too low for conducting further analyses. NRT (n=413, 71.21%) was used more commonly compared to Varenicline (n=167, 28.79%). Most of the cessation medications were prescribed by their primary care physicians (n=562, 96.90%) and about forty percent of the patients had received smoking counseling from their healthcare providers anytime one year prior to index date (n=231, 39.83%).

Among the 580 patients, a total of 276 (47.59%) had elevated glucose/cholesterol/blood pressure from week 12 up to one year after the cessation medication exposure. The association between all the independent variables and the outcome can also be found in table 1.

Predictors for developing metabolic syndromes during 1-year follow up time period

All the independent variables in the model met Schoenfield assumption and no interactions were found between the cessation medications and other independent variables using chunck test so there were no need for further adjustments. We found that those whose index mediation was NRT had lower risks in developing cardiovascular risk factors (HR=0.71, 95% CI=0.54 -0.94) compared to those who were prescribed Varenicline. Males (HR=1.47, 95% CI=1.14 -1.89), obese adults (HR=1.63, 95% CI=1.24 -2.15), and those with high comorbidity indices (HR=1.17, 95% CI=1.08 -1.26) had higher risks in developing elevated glucose/cholesterol/blood pressure. Other significant characteristics that we found significantly affect metabolic syndromes included being male gender, obesity, and with higher comorbidity index. Please see table 2 for our multivariate PH regression results.

| Table 2: Predictors for developing elevated glucose/cholesterol/blood pressure during 1-year follow up. | ||

| Characteristics | Elevated glucose/cholesterol/blood pressure (n=276, 47.59%) | |

| Unadjusted HRs | Adjusted HRs | |

| Demographics | ||

| Sex Female Male |

Reference 1.34 (1.05-1.70)* |

Reference 1.47 (1.14-1.89)* |

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) |

| Race Blacks Whites All others |

Reference 1.21 (0.82-1.78) 1.05 (0.72-1.55) |

Reference 1.26 (0.82-1.92) 1.05 (0.69-1.61) |

| Region Midwest Northeast South West |

Reference 1.03 (0.78-1.37) 0.89 (0.62-1.28) 0.84 (0.60-1.20) |

Reference 0.98 (0.72-1.35) 0.79 (0.53-1.19) 0.76 (0.52-1.10) |

| BMI Normal (BMI<25) Overweight (25<=BMI<30) Obesity (BMI>=30) |

Reference 0.99 (0.72-1.38) 1.47 (1.13-1.91)* |

Reference 0.98 (0.70-1.38) 1.63 (1.24-2.15)* |

| Insurance Not Medicare/Medicaid Medicare or Medicaid |

Reference 1.12 (0.88-1.42) |

Reference 1.11 (0.86-1.42) |

| Clinical factors | ||

| Comorbidty Index | 1.13 (1.06-1.21)* | 1.17 (1.08-1.26)* |

| Had antipsychotic injectables 1 year prior to index date No Yes |

Reference 0.61 (0.30-1.22) |

Reference 0.53 (0.26-1.07) |

| Smoking Cessation Related | ||

| Addicted to nicotine (# of cigarettes smoked per day ≥1) No Yes |

Reference 1.15 (0.84-1.59) |

Reference 1.09 (0.77-1.56) |

| Cessation Medication Varenicline NRT |

Reference 0.81 (0.63-1.03) |

Reference 0.71 (0.54-0.94)* |

| Cessation Rx given by specialty care physician? No Yes |

Reference 0.63 (0.28-1.40) |

Reference 0.70 (0.31-1.59) |

| Received any medication that might affect smoking status anytime 1 year prior to index date No Yes |

Reference 0.71 (0.42-1.21) |

Reference 0.74 (0.43-1.27) |

| Smoking counseling received anytime one year prior to index date No Yes |

Reference 0.95 (0.74-1.20) |

Reference 0.90 (0.70 -1.16) |

| * p≤0.05 | ||

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that examined the relationship between cessation medications and several metabolic syndromes among schizophrenic patients. We found nearly half (n=276, 47.59%) of the 580 cohort developed one or more criteria of metabolic syndromes within just one year after cessation medication exposure. The rate of metabolic syndrome found in our study was extremely high and is in need of addressing. De Hert et al. [31] conducted a study among schizophrenic patients in 2006. They found that after the SGA exposure, 26.5% developed metabolic syndromes during 3.2 years of follow up. Our follow up timeline was one year only but the incidence rate was almost doubled than that in their study. This indicated that our cohort population is under higher risks and could be possibly due to side effects of both antipsychotics and cessation medications. We need to pay close attention because individuals with the metabolic syndrome have a 61% increased risk of cardiovascular disease compared to those without [32].

We found smokers who were prescribed NRT were less likely to develop cardiovascular risk factors as compared to those who were prescribed Varenicline (HR=0.71, 95% CI=0.54-0.94). This indicates that Varenicline might have some drug interactions with the antipsychotics patients were already taking. The mechanism behind Varenicline leading to cardiovascular risk is still unknown but its label was updated accordingly with warnings of elevated cardiovascular events. It’s not surprising that hazard ratios for NRTs were less in comparison to Varenicline since NRTs are mainly OTCs and are generally considered to be safer. Therefore, healthcare professionals are advised to carefully weigh the risks of Varenicline against the benefits before its use. Patients should contact their physicians if they experience any chest pain or shortness of breath symptoms when taking the medication. Physicians should also advise their patients to have their blood work done regularly so we could make sure their blood glucose levels and cholesterol levels are under good control. Life style should be adjusted if they were to find some of the cardiovascular indicators exceed the normal ranges [33].

Several trials have demonstrated a lesser post cessation weight gain when using Bupropion among the general population [14,34]. Participants taking Bupropion were found to gain significantly less weight than those on placebo [14,35]. This indicated when schizophrenic patients are considering quitting, Bupropion might be a better option for those who have family histories of diabetes, hyperlipidemia or high blood pressure. Future studies should include more patients who tried to quit with Bupropion so it could be tested in this minority population.

We found higher levels of BMI and comorbidity index were more likely to develop cardiovascular risks. These findings were expected because BMI is reported to be positively associated with hypertension and dyslipidemia, and obesity is associated with diabetes [36]. It is estimated that for every 1-kg increase in weight, the prevalence of diabetes increases by 9% [37]. Similarly, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease among people in the normal weight, overweight, and obese groups is 20%, 28%, and 39%, respectively [38].

We also found males were more likely to develop elevated glucose/cholesterol/blood pressure than females (HR=1.47, 95% CI=1.14-1.89). Sex differences in cardiovascular risks have been discussed in previous research and the findings varied among studies. North American surveys indicate that cardiovascular diseases are more prevalent in men, with 8.4% of men vs. 5.6% of women in the U.S.; however, the incidence has been declining in men and remained stable in women. Possible reasons for gender association with cardiovascular disease include higher rates of overweight and cigarettes smoking for men; on the other hand, reasons for females include less physically activity and diminishing estrogen levels during premenopausal and menopausal phase. Adolescent girls and premenopausal women tend to have more favorable risk profiles with lower levels in cholesterol and glucose [39]. However, levels plateau in men and increase in women between ages 40 and 60 years [39]. This increase at menopause is thought to be partly the result of advancing age and declining levels of estrogen [39].

Strengths and limitations

The limitations are mainly related to EMR data: (1) we could not track if patients picked up the medication at a pharmacy. Medication data were identified by physician orders, which did not guarantee patients actually filled the prescription. (2) We are not certain how compliant the patients were. Unlike chronic medications, cessation products are for a short term use, so compliance should not be a significant problem [40]. (3) Some important variables were with missing information, for example, the stop dates of medications were not recorded. With missing values, it is difficult to generalize our findings. Furthermore, some possible confounders were not recorded in GE data like eating habits, physical activities, or family history for some diseases. (4) We might underestimate the percentage of those on NRT because majority of products are over the counter. Smokers might not mention that information to their doctors if not being asked; therefore, it would not be recorded in GE EMR.

Given the limitations above, the population distribution in GE is very similar with the US population and thus is representativeness of outpatient practice. It is also rich in clinical information including vital signs, laboratory results, medications/prescriptions, and diagnoses. With proper smoking cessation medications information (including NRT OTCs), it was considered an appropriate database for our research question. No studies have been conducted with this population examining the associations between cessation medications and cardiovascular risks. Our findings are important to fill the gap in research as warnings were noticed for general populations and not to mention for this minority sub-group who are already under higher risks.

Conclusions

Individuals with metabolic syndromes have high risk of developing cardiovascular diseases in the future. In our study, we found nearly half (n=276, 47.59%) of the 580 cohort developed one or more criteria of metabolic syndromes within just one year after the cessation medication. Bupropion was not included in this analysis because of low sample size and we found smokers who were prescribed NRT were less likely to develop metabolic syndromes as compared to those who were prescribed Varenicline. Since the rates of developing metabolic syndromes are so high, healthcare professionals are advised to carefully weigh the risks of cessation medications against the benefits before use. Other predictors we found that were associated with cardiovascular risks included being male gender, with higher levels of BMI and comorbidity index.

Declaration

This manuscript has not been published elsewhere and that it has not been submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the IRB at the University of Houston.

References

- Evins AE, Cather C, Culhane MA, Birnbaum A, Horowitz J, et al. A 12-week double-blind, placebo controlled study of bupropion SR added to high-dose dual nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation or reduction in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007; 27: 380-386. Ref.: https://goo.gl/T6KsxS

- Ferchiou A, Szöke A, Laguerre A, Méary A, Leboyer M, et al. Exploring the relationships between tobacco smoking and schizophrenia in first-degree relatives. Psychiatry Res. 2012; 200: 674-678. Ref.: https://goo.gl/sBbFCb

- George TP, Vessicchio JC, Sacco KA, Weinberger AH, Dudas MM, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion combined with nicotine patch for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2008; 63: 1092-1096. Ref.: https://goo.gl/34Sxoh

- Lo S, Heishman SJ, Raley H, Wright K, Wehring HJ, et al. Tobacco craving in smokers with and without schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 2011; 127: 241-245. Ref.: https://goo.gl/kJ9FJX

- Leonard S, Mexal S, Freedman R. Smoking, genetics and schizophrenia: evidence for self medication. J Dual Diagnosis. 2007; 3: 43-59. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ee3xqr

- Tsoi DT, Porwal M, Webster AC. Efficacy and safety of bupropion for smoking cessation and reduction in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis.British J Psychiatry. 2010; 196: 346-353. Ref.: https://goo.gl/zTx4rB

- 7.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. Impact of over-the-counter sales on effectiveness of pharmaceutical aids for smoking cessation. JAMA. 2002; 288: 1260-1264. Ref.: https://goo.gl/o1Esp6

- Jimenez-Ruiz C, Berlin I, Hering T. Varenicline: a novel pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Drugs. 2009; 69: 1319-1338. Ref.: https://goo.gl/8roqNE

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, Clayton A, Stahl SM, et al. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Primary Care Com J Clinical Psyc. 2005; 7: 106-113. Ref.: https://goo.gl/pkbryL

- Fiore, Michael C. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical practice guideline. DIANE Publishing. 2008; Ref.: https://goo.gl/XpbSLR

- Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD. Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011; 183: 1359-1366. Ref.: https://goo.gl/pU4Jhf

- Erhardt L. Cigarette smoking: an undertreated risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009; 205: 23-32. Ref.: https://goo.gl/E5ddsG

- Filozof C, Pinilla F, Fernández-Cruz A. Smoking cessation and weight gain. Obesity Reviews. 2004; 5: 95-103. Ref.: https://goo.gl/9eeXaa

- Parsons AC, Shraim M, Inglis J, Aveyard P, Hajek P. Interventions for preventing weight gain after smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; 1. Ref.: https://goo.gl/kR6Qzk

- Yeh HC, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Wang NY, Brancati FL. Smoking, Smoking Cessation, and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus A Cohort Study. Ann Internal Medicine. 2010; 152: 10-17. Ref.: https://goo.gl/rdgtMA

- Janzon E, Hedblad B, Berglund G, Engström G. Changes in blood pressure and body weight following smoking cessation in women. J iIternal Med. 2004; 255: 266-272. Ref.: https://goo.gl/reut8M

- Gerace TA, Hollis J, Ockene JK, Svendsen K. Smoking cessation and change in diastolic blood pressure, body weight, and plasma lipids. Preventive Medicine. 1991; 20: 602-620. Ref.: https://goo.gl/2KqfuQ

- Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, Hunger H, Schmid F, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Res. 2010; 123: 225-233. Ref.: https://goo.gl/F6uc7v

- Chakos M, Lieberman J, Hoffman E, Bradford D, Sheitman B. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. FOCUS: The J Lifelong Learning in Psy. 2004; 2: 111-121. Ref.: https://goo.gl/n4GsTm

- Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction, smoking-induced disease, and therapeutics. Ann Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009; 49: 57. Ref.: https://goo.gl/UwUvFA

- Evins AE, Cather C, Deckersbach T, Freudenreich O, Culhane MA, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. J Clinical Psyc. 2005; 25: 218-225. Ref.: https://goo.gl/DM1YGN

- Zammit S, Allebeck P, David AS, Dalman C, Hemmingsson T, et al. A longitudinal study of premorbid IQ score and risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and other nonaffective psychoses. Arch General Psy. 2004; 61: 354-360. Ref.: https://goo.gl/39AoQh

- Lund BC, Perry PJ, Brooks JM, Arndt S. Clozapine use in patients with schizophrenia and the risk of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension: a claims-based approach. Arch General Psyc. 2001; 58: 1172. Ref.: https://goo.gl/L2Djw1

- Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, et al. The Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular RiskA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J American College of Card. 2010; 56: 1113-1132. Ref.: https://goo.gl/fXUFCm

- Rigotti NA, Pipe AL, Benowitz NL, Arteaga C, Garza D, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Varenicline for Smoking Cessation in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease A Randomized Trial. Circulation. 2010; 121: 221-229. Ref.: https://goo.gl/LgwNxF

- Cleland JG, Gemmell I, Khand A, Boddy A. Is the prognosis of heart failure improving?. European J Heart Failure. 1999; 1: 229-241. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ug1w5u

- Lambert BL, Cunningham FE, Miller DR, Dalack GW, Hur K. Diabetes risk associated with use of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in veterans health administration patients with schizophrenia. Am I Epidemiol. 2006; 164: 672-681. Ref.: https://goo.gl/EHSSYA

- Lin HC, Chien CW, Ho JD. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus and the risk of stroke A population-based follow-up study. Neuro. 2010; 74: 792-797. Ref.: https://goo.gl/LBd4Fy

- de Leon J, Correa JC, Ruaño G, Windemuth A, Arranz MJ, et al. Exploring genetic variations that may be associated with the direct effects of some antipsychotics on lipid levels. Schizophrenia Res. 2008; 98: 40-46. Ref.: https://goo.gl/fBPdy6

- Lambert BL, Chou CH, Chang KY, Tafesse E, Carson W. Antipsychotic exposure and type 2 diabetes among patients with schizophrenia: a matched case-control study of California Medicaid claims. Pharma Drug Saf. 2005; 14: 417-425. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Lwsj2W

- De Hert M, Schreurs V, Sweers K, Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, et al. Typical and atypical antipsychotics differentially affect long-term incidence rates of the metabolic syndrome in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a retrospective chart review. Schizophrenia Res. 2008; 101: 295-303. Ref.: https://goo.gl/7mijz1

- Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. The Am J Med. 2006; 119: 812-819. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ehN3CD

- Stone NJ, Saxon D, Approach to treatment of the patient with metabolic syndrome: lifestyle therapy. The Am I Cardiol. 2005; 96: 15-21. Ref.: https://goo.gl/tdc1CA

- Gadde KM, Xiong GL. Bupropion for weight reduction. Expert Rev Neurotherapeutics. 2007; 7: 17-24. Ref.: https://goo.gl/LgqXjQ

- Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Rennard SI, Johnston JA, et al. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. New England J Med. 1999; 340: 685-691. Ref.: https://goo.gl/eKoVD5

- Paeratakul S, Lovejoy JC, Ryan DH, Bray GA. The relation of gender, race and socioeconomic status to obesity and obesity comorbidities in a sample of US adults. Int J Obesity & Rel Metabolic Dis. 2002; 26: 1205-1210. Ref.: https://goo.gl/iirb5a

- Sullivan PW, Morrato EH, Ghushchyan V, Wyatt HR, Hill JO. Obesity, inactivity, and the prevalence of diabetes and diabetes-related cardiovascular comorbidities in the US, 2000–2002. Diabetes Care. 2005; 28: 1599-1603. Ref.: https://goo.gl/gW2j5d

- Wang G, Zheng ZJ, Heath G, Macera C, Pratt M, et al. Economic burden of cardiovascular disease associated with excess body weight in US adults. Am J Preventive Med. 2002; 23: 1-6. Ref.: https://goo.gl/JpVZYL

- Pilote L, Dasgupta K, Guru V, Humphries KH, McGrath J, et al. A comprehensive view of sex-specific issues related to cardiovascular disease. CMAJ. 2007; 176: 1-44. Ref.: https://goo.gl/aCYmbB

- Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, Denekens J. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharmacy Ther. 2001; 26: 331-342. Ref.: https://goo.gl/NJU4Bk